Intro

I was recently invited by the academic team “DN” (the name, surprisingly, has no inappropriate connotation) to compete in Mentor High School’s second CTF iteration, MHSCTF 2023. Although the competition ran for 15 days, we maxed out their 11 challenges in just under 16 hours (ignoring solve resets) and managed to take first place. This writeup was part of the verification process, which came with prize-receiving — enjoy!

Matchmaker

I’ve just had the most brilliant idea 😮 I want to write a program that takes all the students and how much they like each other to pair them up so I can maximize the total love in the classroom! Of course, when I say “I,” I really mean… “you” 😉

Notes: [SEE BELOW]

nc 0.cloud.chals.io [PORT]

Warning: Discrete math, graph theory, and combinatorial optimization ahead! If you’re unfamiliar with the mathematical symbols used in this writeup, reference this dropdown:

Complicated Math Symbols

- - Summation

- - Element of

- - Not an element of

- - Proper subset of

- - Subset of

- - Empty set

- - For all

- - There exists

- - There does not exist

- - Element of

- - Not an element of

- - Contains as member

- - Does not contain as member

- - Set minus (drop)

- - Direct sum

- - Union

- - Intersection

- - Prime

First blood! Here are the notes the author provided alongside the challenge description, abridged for brevity:

- The connection times out after 60 seconds, and there will be 3 iterations.

- The input will be given in lines, where represents the number of students. The first line represents the zeroth student, the second line represents the first student, and so on (, ).

- Each line of input contains integers (ranged , inclusive); represents a student’s rating of another student at that index, repeated for everybody but themselves.

I’ve cut the notes provided in half to make it a bit more digestable. Before we continue, let’s see some sample input from the server for context:

from pwn import *

p = remote('0.cloud.chals.io', [PORT])

print(p.recvuntilS(b'> '))$ python3 matchmaker.py

[+] Opening connection to 0.cloud.chals.io on port [PORT]: Done

86 60 67 84 44 4 36 59 100 63 51 6 92 66 36 99 3 69 55 11 21 66 66 81 21 63 76 44 4 87 13 67 0 97 28 13 68 96 47 49 0 18 63 26 73 68 13 63 47 61 0 53 74 56 6 12 5 66 54 47 79 81 84 43 19 6 62 52 6 100 86 64 1 4 38 89 93 6 72 93 63 46 90 29 81 89 5 9 77 23 87 94 73

76 0 74 52 56 60 57 78 48 93 85 66 29 70 96 40 76 62 46 66 69 31 99 47 12 42 43 12 47 19 26 8 26 45 29 27 17 14 15 54 57 78 69 73 55 16 88 50 96 97 34 49 78 3 91 53 28 66 28 28 9 38 87 20 66 28 37 38 94 61 96 99 45 39 52 5 27 5 96 41 31 83 86 32 92 35 96 10 2 97 3 19 88We can do a bit of analysis on what we’ve received so far.

The first line, 86 60 67..., can be translated into:

- Student 0 -> Student 1 = 86

- Student 0 -> Student 2 = 60

- Student 0 -> Student 3 = 67

Let’s do the same thing for the second line, 76 0 74...:

- Student 1 -> Student 0 = 76

- Student 1 -> Student 2 = 0

- Student 1 -> Student 3 = 74

Notice how the student will always skip their own index, which aligns with the author’s notes detailing how the integers “represent the students ratings of everybody but themselves.” Let’s continue with the rest of the notes:

- Determine the pairings that maximize the students’ ratings for each other

- Example: If Student 1 -> Student 7 = 98 and Student 7 -> Student 1 = 87, and Students 1 and 7 are paired, the score of this pairing would be

- The output should list all maximized pairs (including duplicates; order of the pairs does not matter)

- Example: If Student 0 -> Student 3, Student 1 -> Student 2, and Student 4 -> Student 5, the desired output is:

0,3;1,2;2,1;3,0;4,5;5,4 - The connection will close if the output is incorrect, and reiterate if correct

Let’s crack on with the actual algorithm which will be used for solving this!

Graph Theory Fundamentals

This challenge is a classic example of a concept called “maximum weight matching,” which is fundamental in graph theory and discrete mathematics. Although there is a relatively high prerequisite knowledge floor for understanding these concepts, I’ll explain them as best as I can.

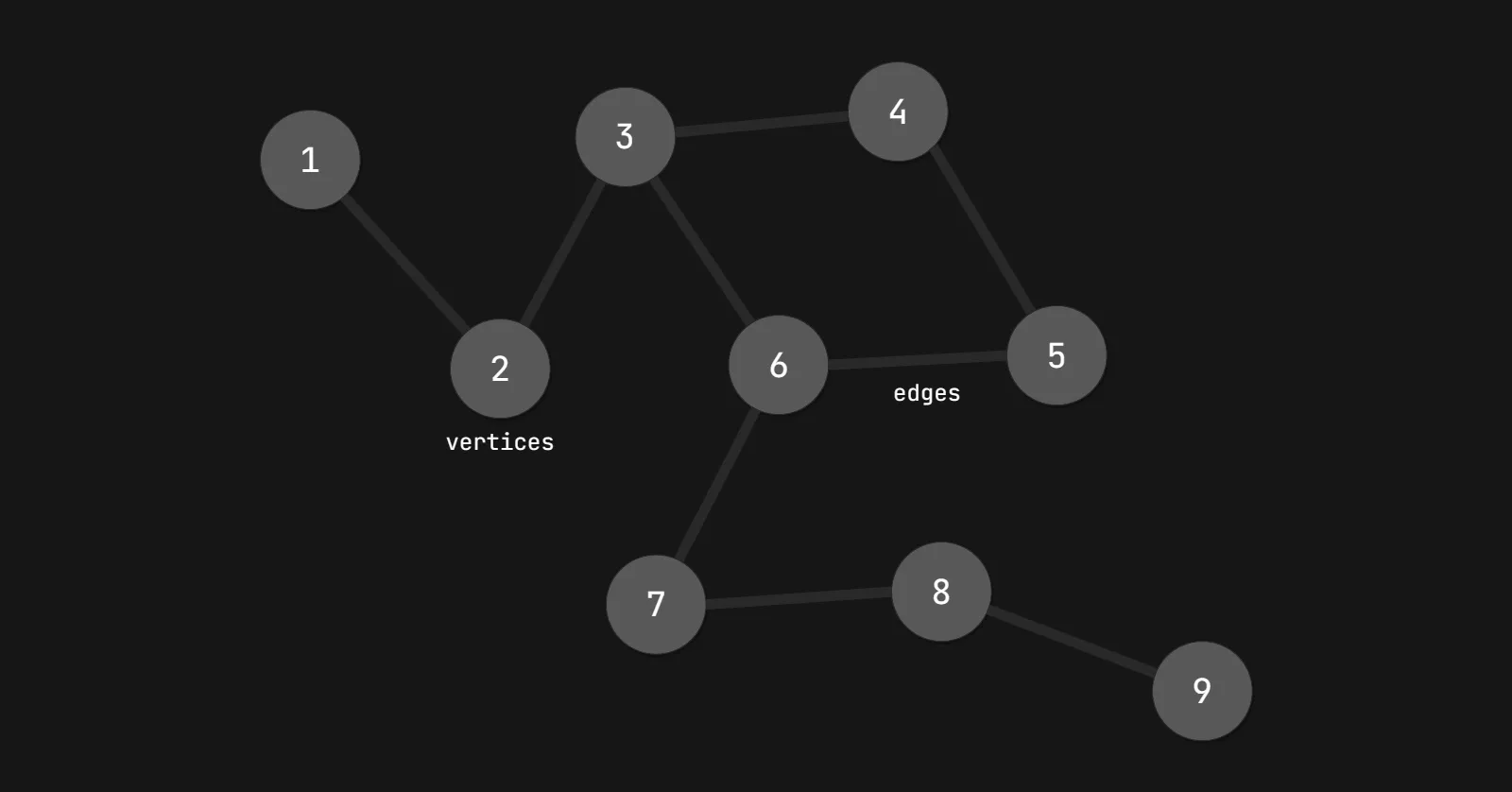

Firstly, let’s define a graph. A graph is a set of vertices (or nodes), which are connected by edges. Not to be confused with the Cartesian coordinate system, graphs are represented by the ordered pair in which is a set of vertices and is a set of edges:

A set of edges is defined as:

By this definition, and are the vertices that are connected to the edge , called the endpoints. It can also be said that is incident to and .

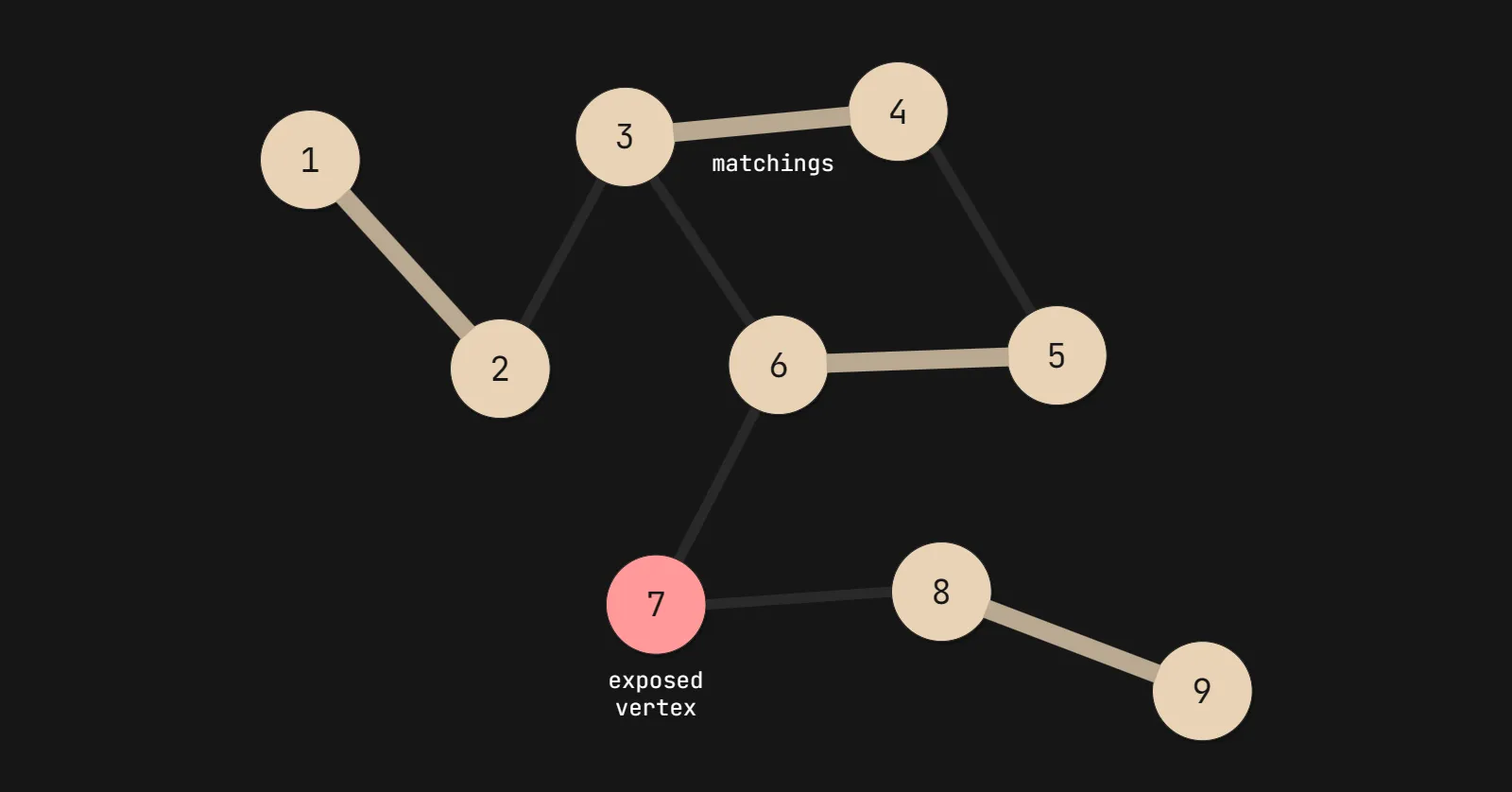

We can create a matching within the graph , in which is a collection of edges such that every vertex of is incident to at most one edge of (meaning two edges cannot share the same vertex). When the highest possible cardinality (number of matches) of is reached, the matching is considered maximum, and any vertex not incident to any edge in is considered exposed.

Formally, a matching is said to be maximum if for any other matching , . In other words, is the largest matching possible.

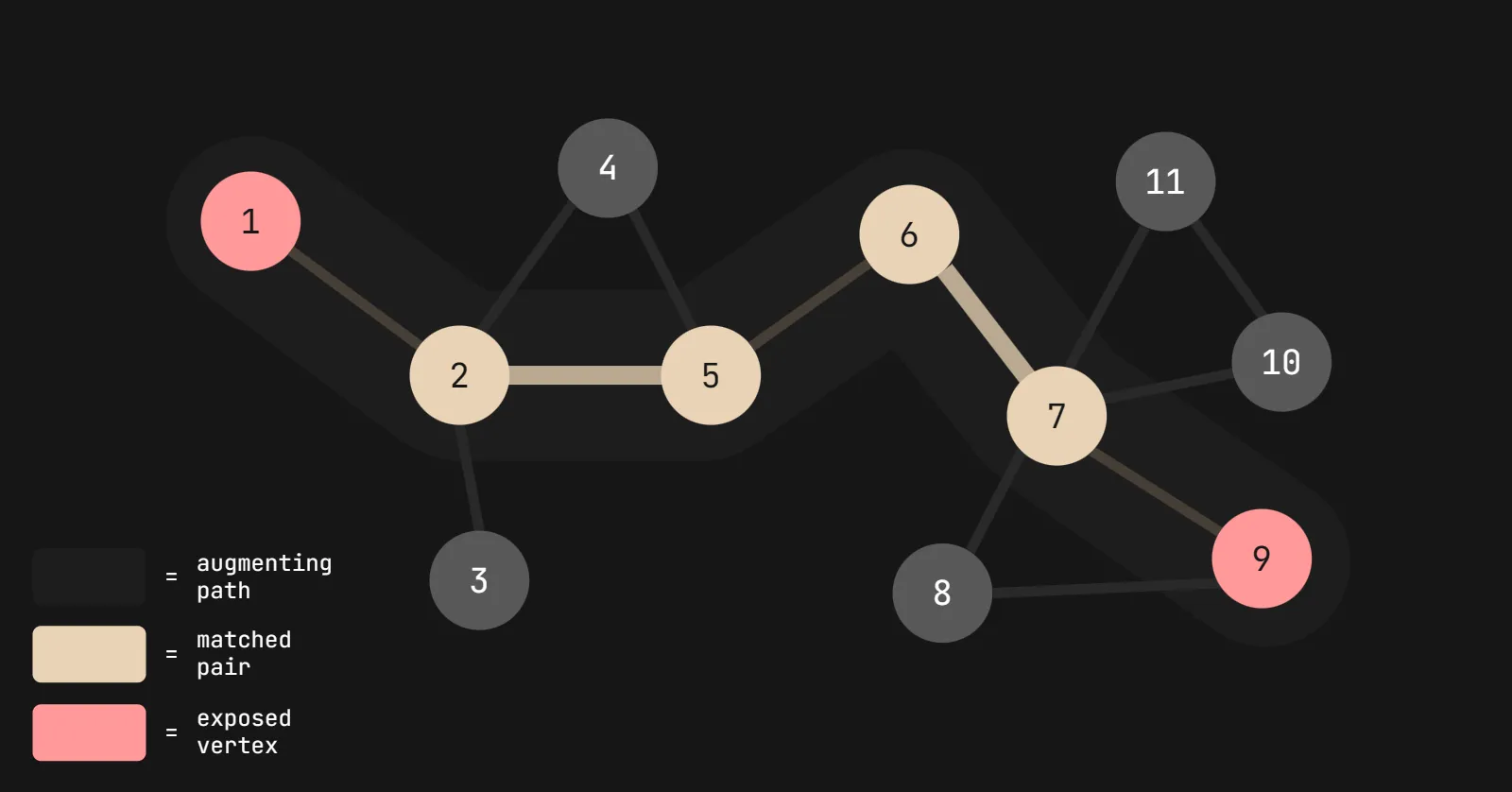

For example, the following is a maximum matching performed on the graph above:

Since there is an exposed vertex in this graph (and because the size of is odd), is not considered perfect. A perfect maximum matching occurs when the size of is even (or ) and there are no exposed vertices.

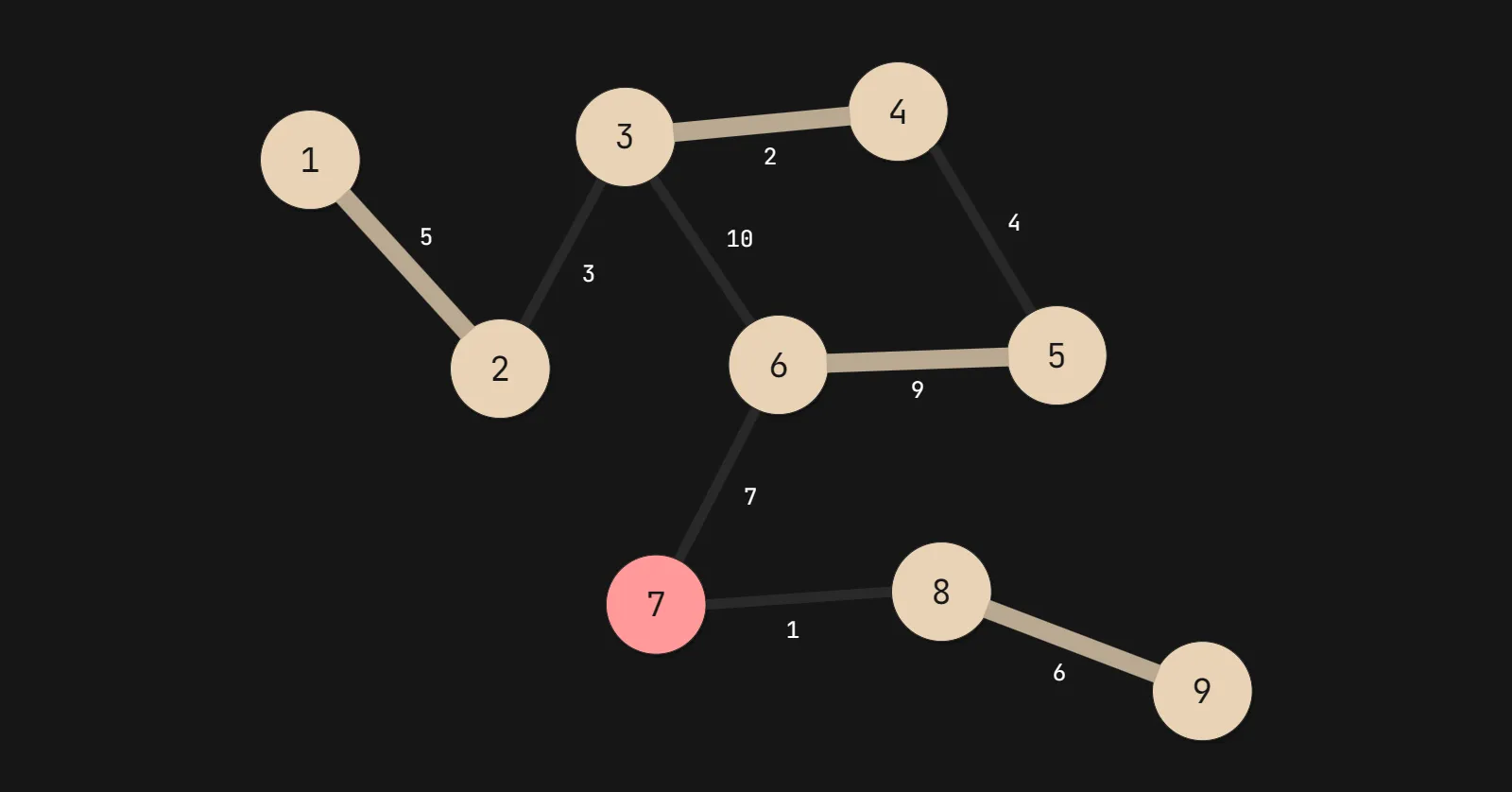

Now, let’s put weights into consideration (i.e. the students’ ratings). With a weighted graph , we can attribute a function that assigns a weight to each edge (defining ):

The total weight of a matching , written as , can be defined as:

Solving for in the example graph above:

Our goal is to maximize — it is definitely not maximized above, since is not at its highest possible value. We will be tackling it with a combination of two different concepts: Edmonds’ blossom algorithm, and the primal-dual method. Although the blossom algorithm is typically meant for maximum cardinality matching (maximizing the size of itself, and running in time), utilizing it as a subroutine alongside the primal-dual method of linear programming creates a maximum weight matching (and running in time).

Firstly, let’s get started with how it works.

The Blossom Algorithm

The core idea behind the blossom algorithm itself involves two concepts: augmenting paths and blossoms (alongside blossom contraction).

Augmenting Paths

Given a graph , a path in can be considered an alternating path if edges in the path are alternatively in and not in . Augmenting paths are a type of alternating, odd-length path that starts and ends with two exposed vertices:

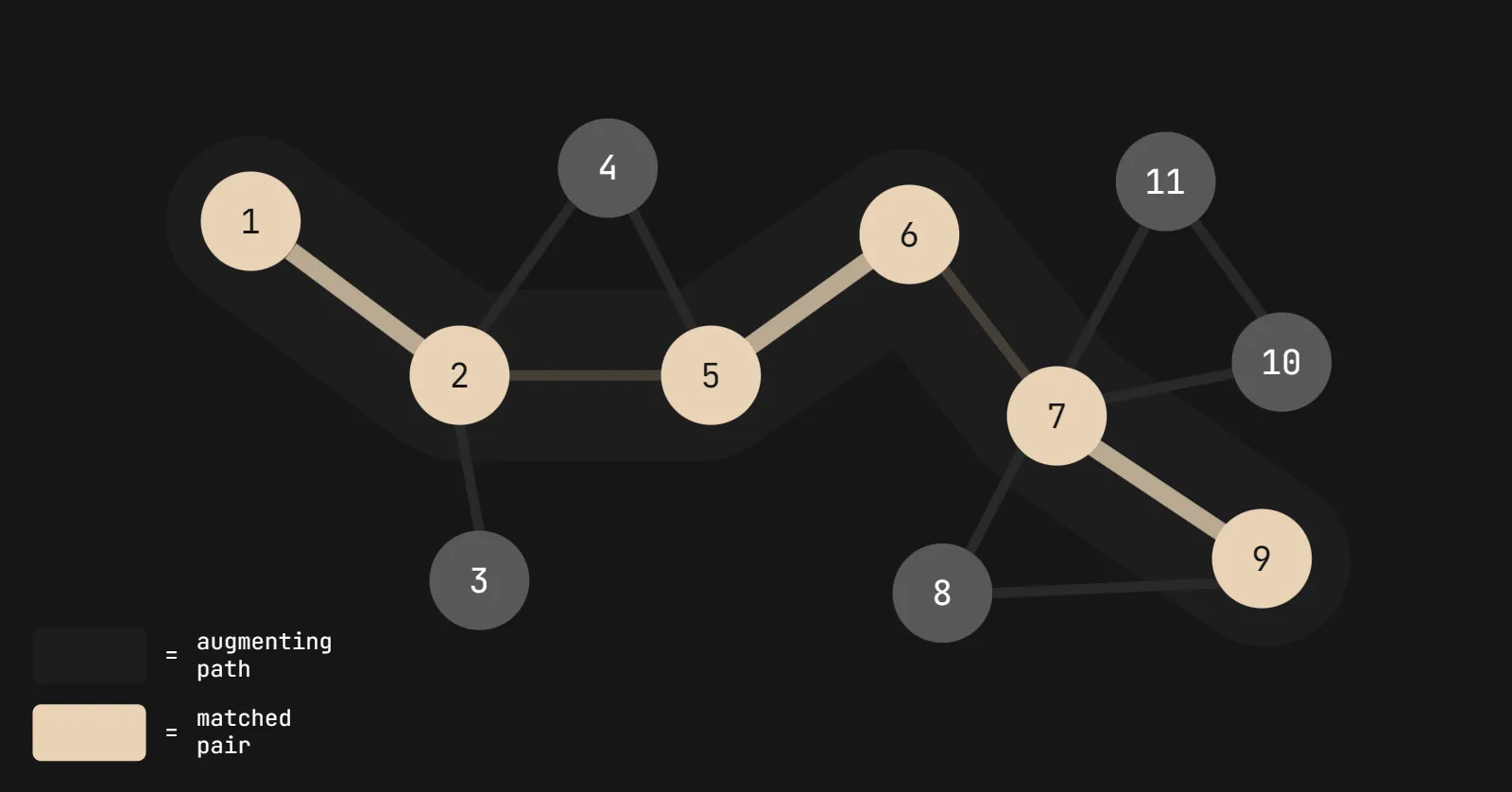

As we can see, is considered an augmenting path because it ends with two exposed vertices. Augmenting paths are special in that they can augment (“to improve”, as per the name) the size of by one edge. To do so, simply swap the edges in that are in with the edges that are not in :

A matching augmentation along an augmenting path is a process by which is replaced by , defined as such:

This implies that .

The reason why augmenting paths are so fundamental to the blossom algorithm is that it directly computes a maximum matching — we can reiterate the process of finding augmenting paths until no more are available in . This is described well with Berge’s Theorem:

Theorem: A matching in a graph is maximum if and only if there is no -augmenting path in .

Here is high-level pseudocode which describes this recursive iteration:

procedure find_maximum_matching(G, M)

P = find_augmenting_path(G, M)

if P == [] then

return M

else

MP = augment_matching(M, P)

return find_maximum_matching(G, MP)

end if

end procedureNote: Under the context of the above pseudocode, find_augmenting_path(G, M) will always start at an exposed vertex, running a breadth-first search to find an augmenting path.

Therefore, the blossom algorithm will always terminate with a maximum matching.

Blossoms (and Blossom Contraction)

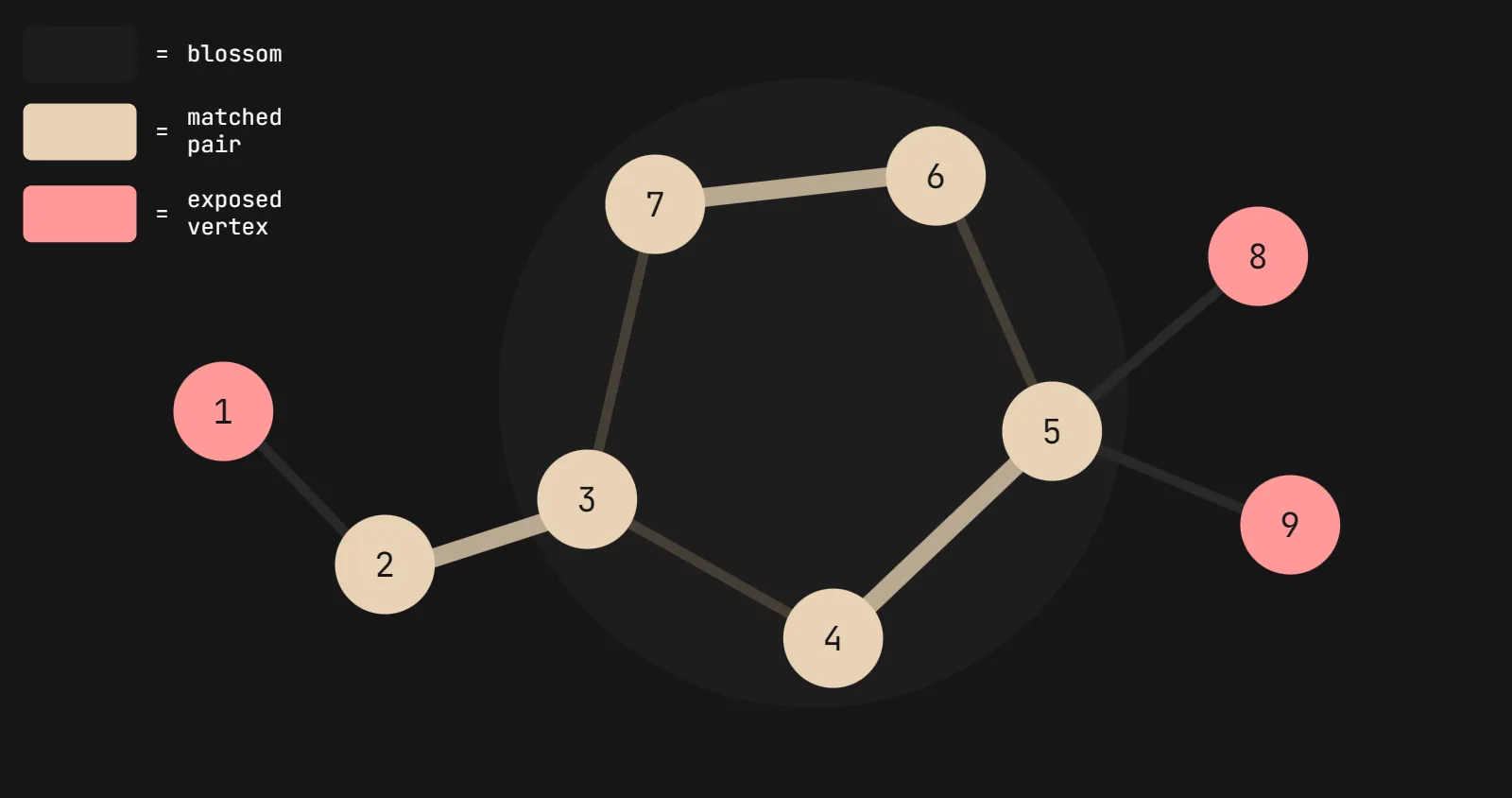

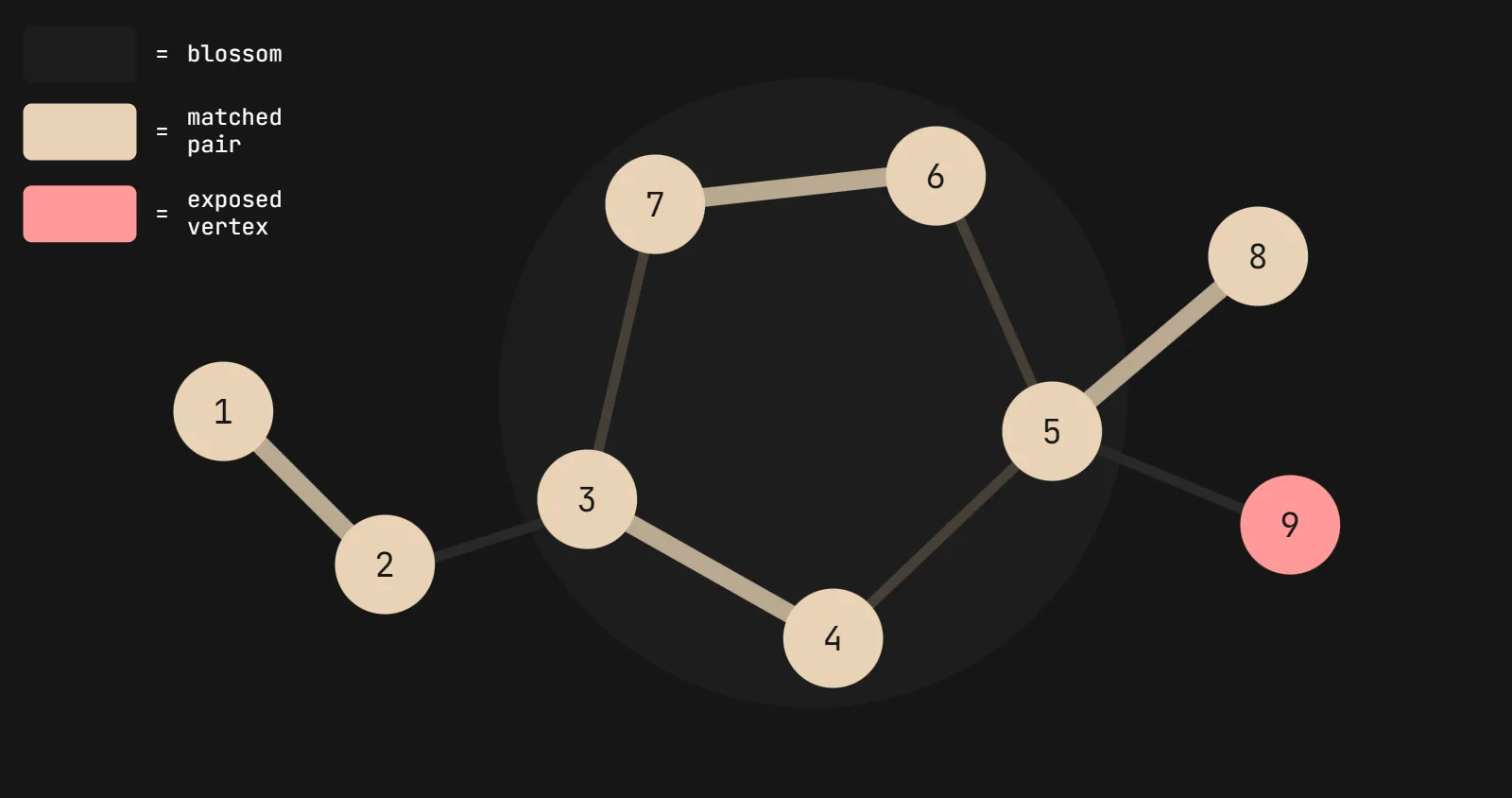

The second concept that we need to understand are blossoms. Given a graph and a matching , a blossom is a “cycle” within which consists of edges, of which exactly belong to (a blossom with two matches would have edges).

Let’s say the algorithm created matchings in a graph with a blossom — although it isn’t the maximum matching possible, we cannot augment it any further because the technically available augmenting path is longer than the shortest available path, therefore terminating subotimally:

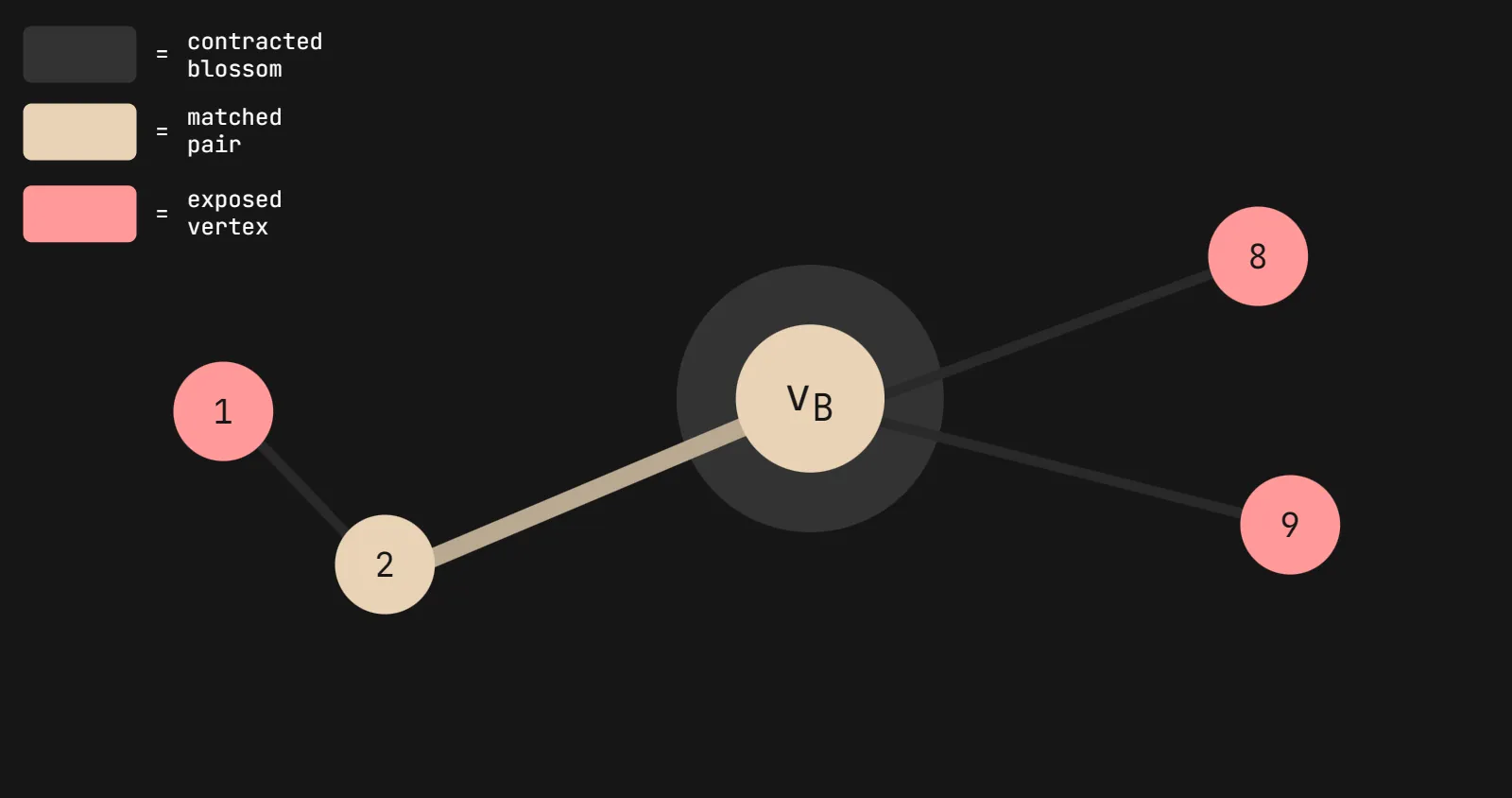

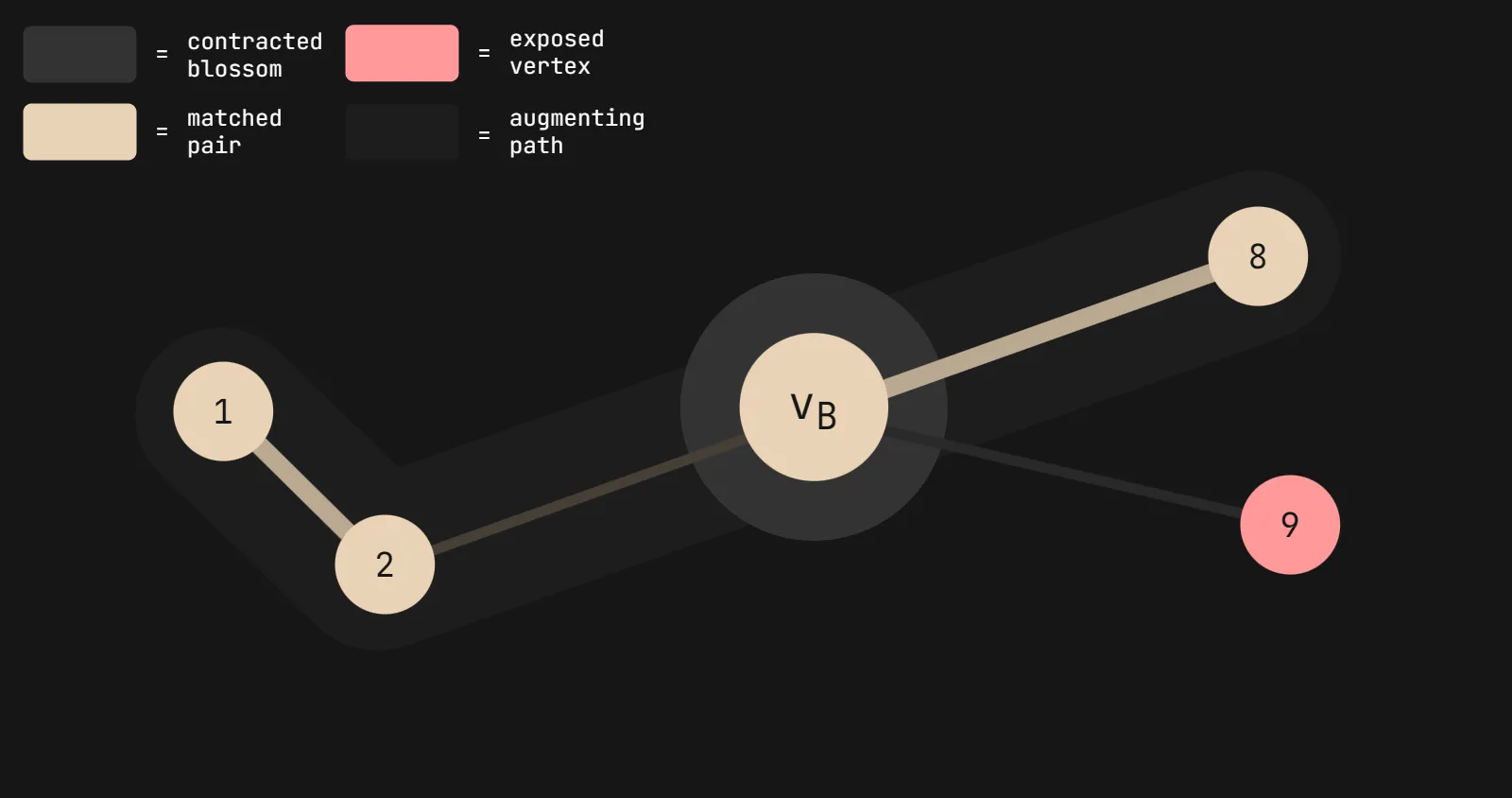

This is where blossom contraction comes in. The idea is to contract the blossom into a single “super-vertex” , and to treat it as a single vertex in the graph:

From there, we can find valid augmenting paths to augment :

Finally, we can expand the blossom back into its original form, to reveal the maximum matching:

Theorem: If a the graph formed after contraction of a blossom in , then has an augmenting path if and only if has an augmenting path.

(This is called the Blossoms Theorem, or the Main Theorem of Botany)

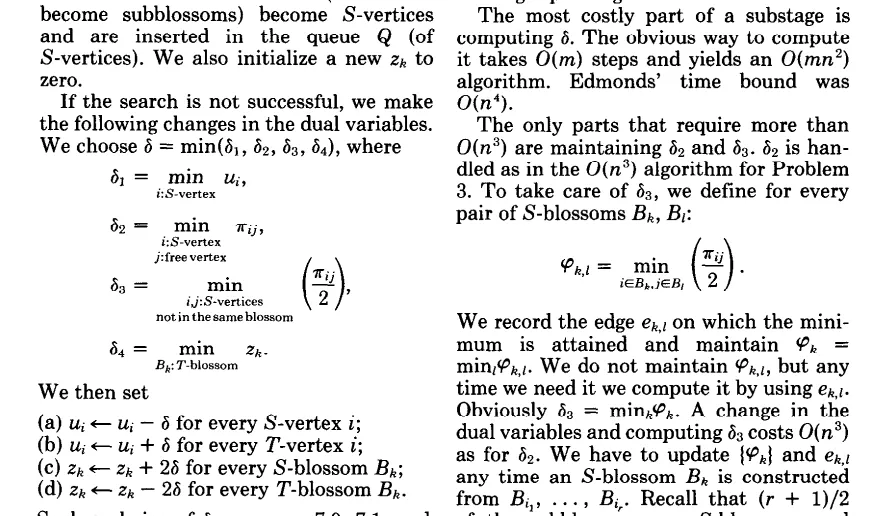

With the fundamental concepts of this beautiful algorithm covered, the only thing we need to wrap our heads around is how to adopt this with weighted graphs. I’ll be referencing Galil’s Efficient Algorithms for Finding Maximum Matching in Graphs for this section.

Primal-Dual Method

So… the primal-dual method. I’ve been personally studying this topic (alongside linear programming in general, from which this method is derived from) for the past couple days after I solved the challenge, and let’s just say that I absolutely have no clue what is going on:

I’ll just sweep it under the rug right now, since we’ll simply be “borrowing” an implementation of the above algorithm to solve this challenge. Let me know if you are knowledgable in this area and would like to contribute to this section!

”Borrowing” an Implementation

Yes, the blossom algorithm is the most elegant thing I’ve ever seen. No, I am absolutely never going to implement it from scratch. I’m not even going to try. Yes, it’s super fun to visualize and understand the concepts, but could you even imagine trying to implement this in code, and deal with “neighbors” and “forests” and “visited nodes?” I can’t.

Currently, we have tried two implementations which work for this challenge in Python3.9: van Rantwijk’s, and the NetworkX Python library. Both run in time, which is still reasonable for our range of , . Duan and Pettie overview an approximate method for maximum weight matching, which runs in linear time.

We’ll begin by parsing the input.

Parsing Input

Let’s start with a quick recap of what the netcat server gave us. We have lines, with representing the amount of students in the classroom (in addition to being an even amount). Each line will contain integers representing the rating that student has for the individual at that index (accommodating for the skipped index representing themselves).

We can pass the input into a variable data with pwntools’s recvuntilS method, which will receive data until it sees the specified string. We’ll use b'> ' as the string to stop at, since that’s the prompt the server gives us.

Once we have the data, let’s convert it into something we can work with — we’ll make a 2x2 matrix so we can access both the student and their rating of another. We should also insert a 0 at the index which the student skipped themselves so the matchings don’t get screwed up:

from pwn import remote

def parse_input(data):

# [:-1] Removes the trailing '> '

data = data.splitlines()[:-1]

data = [x.split() for x in data]

table = [[int(x) for x in row] for row in data]

# Insert 0 at the index which the student skipped themselves

for i in range(len(data)):

table[i].insert(i, 0)

return table

p = remote('0.cloud.chals.io', [PORT])

data = parse_input(p.recvuntilS(b'> '))

print(data)Let’s do some premature optimization and type hinting because I’m a nerd:

from pwn import remote

def parse_input(data: str) -> list[list[int]]:

data = [list(map(int, x.split())) for x in data.splitlines()[:-1]]

[data[i].insert(i, 0) for i in range(len(data))]

return data

def main() -> None:

p = remote('0.cloud.chals.io', [PORT])

data = parse_input(p.recvuntilS(b'> '))

print(data)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()Testing the script:

$ python3 matchmaker.py

[+] Opening connection to 0.cloud.chals.io on port [PORT]: Done

[[0, 39, 79, 40, 92, 6, 36, 10, 23, 53, 22, 1, 95, 23, 28, 53, 12, 19, 21, 89, 91, 17, 1, 45, 9, 37, 97, 68, 40, 96, 69, 17, 50, 98, 79, 33, 44, 18, 38, 31, 33, 84, 94, 64, 11, 64, 24, 82, 25, 0, 72, 99, 51, 58, 85, 60, 81, 68, 68, 93, 73, 51, 84, 56, 19, 48, 5, 69, 38, 55, 74, 81, 41, 0, 64, 42, 1, 60, 47, 89, 64, 26, 96, 10], [3, 0, 8, 70, 90, 46, 65, 81, 94, 86, 22, 56, 48, 66, 0, 13, 73, 61, 71, 86, 25, 98, 40, 58, 79, 84, 80, 99, 17, 75, 60, 74, 39, 18, 77, 4, 63, 96, 29, 68, 54, 44, 2, 48, 59, 34, 24, 18, 95, 13, 3, 53, 40, 70, 28, 60, 13, 59, 72, 74, 47, 30, 94, 48, 82, 61, 58, 41, 84, 88, 67, 64, 8, 0, 97, 22, 86, 2, 93, 4, 55, 53, 15, 70],Nice. Let’s move on to the actual algorithm.

Maximum Weight Matching

This solve utilizes the NetworkX library’s algorithms.matching.max_weight_matching function, which takes a NetworkX Graph class as input (the equivalent of ) and returns a set of tuples (e.g. {(29, 14), (48, 21), (0, 39), (23, 19), ...}) representing the endpoints of the edges in .

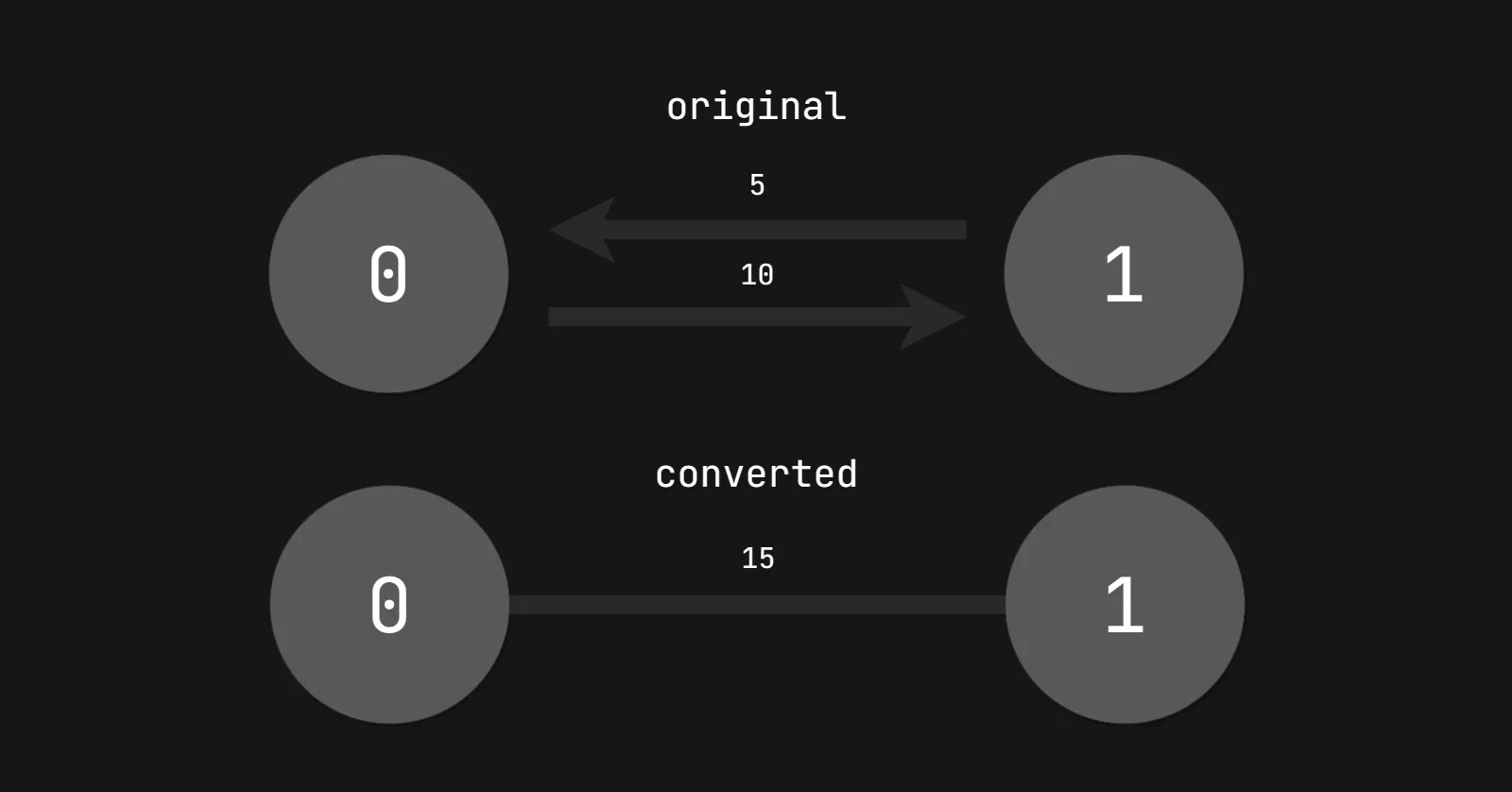

We’ll import networkx.algorithms.matching as matching for our blossom algorithm wrapper, and networkx as nx for our Graph class. In terms of weight, we need to convert the students’ ratings into “biweights” (e.g. ) because the ratings they have for each other aren’t necessarily symmetric:

Each “biweight” now represents the total score of the match, which was mentioned in the author’s notes. We’ll be able to pass this into the max_weight_matching() function as the weight parameter.

To test the algorithm, we’ll use the following dummy input (note that inverse repetition is allowed):

Input: [[0, 0, 100, 0], [0, 100, 0, 0], [0, 100, 0, 0], [100, 0, 0, 0]]

Expected Output: [(0, 3), (1, 2), (2, 1), (3, 0)]In theory, the following script should pair the zeroth student with the third student, and the first student with the second:

from pwn import remote

import networkx as nx

import networkx.algorithms.matching as matching

def parse_input(data: str) -> list[list[int]]:

data = [list(map(int, x.split())) for x in data.splitlines()[:-1]]

[data[i].insert(i, 0) for i in range(len(data))]

return data

def main() -> None:

p = remote('0.cloud.chals.io', [PORT])

data = parse_input(p.recvuntilS(b'> '))

data = [[0, 0, 100, 0], [0, 100, 0, 0], [0, 100, 0, 0], [100, 0, 0, 0]]

G: nx.Graph = nx.Graph([(i, j, {'weight': data[i][j] + data[j][i]}) for i in range(len(data)) for j in range(len(data[i])) if i != j])

M: set[tuple] = matching.max_weight_matching(G, maxcardinality=True)

M_S: list[tuple] = sorted(list(M) + [(b, a) for a, b in M])

print(data)

print(M_S)

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()Testing the script:

$ python3 matchmaker.py

[(0, 3), (1, 2), (2, 1), (3, 0)]The script works locally! Let’s alter it to include the three iterations (alongside the correct formatting, e.g. 0,3;1,2;2,1;3,0;4,5;5,4) so that it can work with the remote server:

from pwn import remote

import networkx as nx

import networkx.algorithms.matching as matching

def parse_input(data: str) -> list[list[int]]:

data = [list(map(int, x.split())) for x in data.splitlines()[:-1]]

[data[i].insert(i, 0) for i in range(len(data))]

return data

def main() -> None:

p = remote('0.cloud.chals.io', [PORT])

for _ in range(3):

data = [[0, 0, 100, 0], [0, 100, 0, 0], [0, 100, 0, 0], [100, 0, 0, 0]]

data = parse_input(p.recvuntilS(b'> '))

G: nx.Graph = nx.Graph([(i, j, {'weight': data[i][j] + data[j][i]}) for i in range(len(data)) for j in range(len(data[i])) if i != j])

M: set[tuple] = matching.max_weight_matching(G, maxcardinality=True)

M_S: list[tuple] = sorted(list(M) + [(b, a) for a, b in M])

result: str = ';'.join([f'{a},{b}' for a, b in M_S])

print(data)

p.sendline(result.encode())

p.interactive()

if __name__ == '__main__':

main()Running the script:

$ python3 matchmaker.py

[+] Opening connection to 0.cloud.chals.io on port [PORT]: Done

[*] Switching to interactive mode

Congratulations! Here's your valentine: valentine{l0V3_i5_1n_7he_4ir}

[*] Got EOF while reading in interactiveWe’ve successfully performed a maximum weight matching utilizing the blossom algorithm and the primal-dual method!

Afterword

Wow, this challenge was definitely a rabbit hole. Even though the author never actually intended for us to go this deep into the math behind it (and for me to skip out on my Calculus classes to learn graph theory and discrete math), I really don’t like ignoring concepts (or in this case, a wrapper function) simply because their prerequisite knowledge floors are either too high or too intimidating. Obviously I was a lost sheep when I was initially researching the blossom algorithm (as this is my first algo challenge, ever), but I just love the feeling when you tear through all the layers abstractions and finally get to the juicy, low-level bits.

I’m glad that our team was able to get first blood one this one, and I’m glad this beautiful algorithm was the first one I’ve learned. I hope you enjoyed this writeup, and I hope you learned something new!

References

- Anstee (UBC): “MATH 523: Primal-Dual Maximum Weight Matching Algorithm” (2012)

- Bader (TUM): “Fundamental Algorithms, Chapter 9: Weighted Graphs (2011)

- Blossom Algorithm (Brilliant)

- Blossom Algorithm (Wikipedia)

- Chakrabarti (Dartmouth): “Maximum Matching” (2005)

- Duan, Pettie: “Linear-Time Approximation for Maximum Weight Matching” (2014)

- Galil: “Efficient Algorithms for Finding Maximum Matching in Graphs” (1986)

- Goemans (MIT): “1. Lecture notes on bipartite matching” (2009)

- Goemans (MIT): “2. Lecture notes on non-bipartite matching” (2015)

- Karp (UC Berkeley): “Edmonds’s Non-Bipartite Matching Algorithm” (2006)”

- Monogon: “Blossom Algorithm for General Matching in O(n^3)” (2021)

- NetworkX Documentation

- Radcliffe (CMU): “Math 301: Matchings in Graphs”

- Shoemaker, Vare: “Edmonds’ Blossom Algorithm” (2016)

- Sláma: “The Blossom algorithm” (2021)

- Stein (Columbia): “Handouts - Matchings” (2016)

- Vazirani (UC Berkeley): “Lecture 3: Maximum Weighted Matchings”

- van Rantwijk: “Maximum Weighted Matching” (2008)